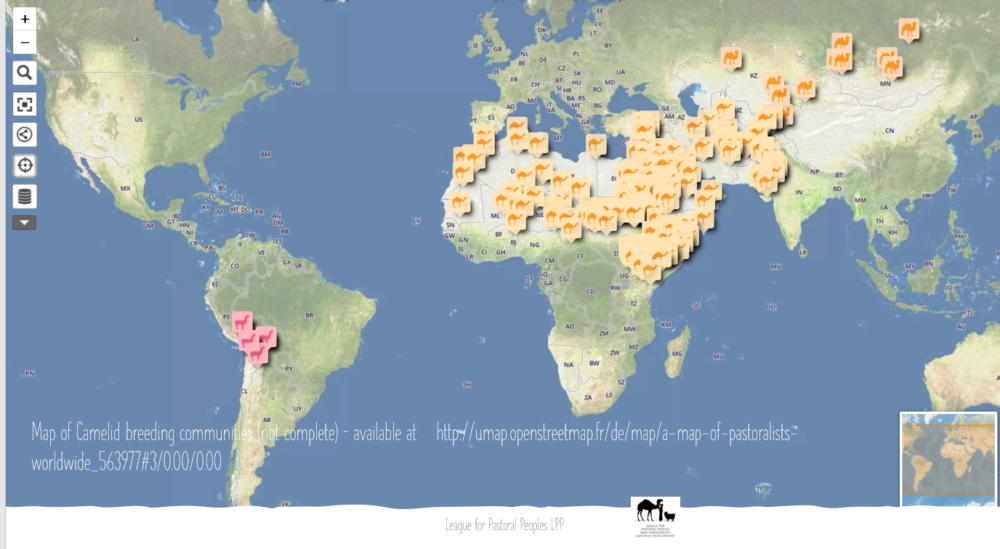

In the ‘Camel and the Wheel‘, Richard Bulliet, a professor of history at Columbia University, describes how, in the Middle East and beyond, camels replaced wheeled transport in the period from around the 4th to the 19th century – for one millenium and a half -, because of their greater utility for long distance transportation and ability to move on rough roads.

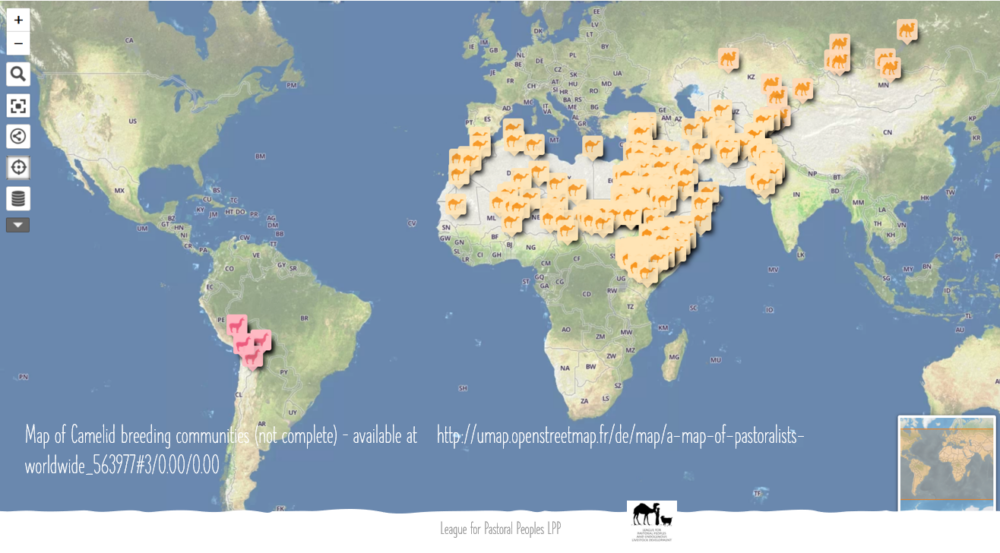

In Maharashtra, a state in Central India, the reverse process is currently playing out: camels are being replaced by bullock carts. During a recent field visit to shepherds around Nagpur facilitated by the Centre for People’s Collective, we met and interacted with Rebari pastoralists who cover around 1000 km a year in Vidarbha district, grazing their sheep and goats on harvested cotton fields and in forests, producing not just protein but also providing much coveted organic manure. Originating from Kutch in Gujarat, they had come a generation earlier bringing along camels to transport their household belongings. But now many of them have switched to bullock carts. The reason: Obtaining male camels from the camel breeding states of Rajasthan and Gujarat is fraught with risk. The Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015 renders it illegal to import camels from Rajasthan without special permission. For Gujarat, no such law exists, but camels are routinely intercepted by animal welfare activists who claim they are going for slaughter, besides arguing that it is an act of cruelty to make camels walk the distance from Gujarat to Maharashtra.

Pack camels have several advantages over bullock carts – they can go anywhere, even in the absence of roads, and they can cover longer distances. They don’t get stuck in the mude like carts do during the monsoon. To be sure, ox carts also have advantages, mainly that they do not have to be loaded and unloaded everytime the family moves. But in the whole, camels provide greater mobility which has positive impacts on the health of the sheep and goats and thereby household income.

At the same time, as shepherds in Maharashtra have to forego the utility of camels for their livelihoods, the Raika camel breeders of Rajasthan and the Rebari and Fakirani Jat of Gujarat are desperate to find a market for their male camels. In fact, the absence of buyers is a major reason for herders to drop out of breeding camels, and is responsible for the drastic decline of the population in Rajasthan. One hears that the Government of India is currently developing a camel policy, including a National Camel Sustainability Initiative, to reverse the trend. For sure, facilitating the movement of camels across state borders rather than obstructing it, would certainly revitalize the camel economy. It is imperative that such measure will be included in this initiative.

It is ironic that the interventions that currently prevent the flow of animals from camel breeding areas to camel using regions in India are enacted for the purpose of camel conservation and welfare. On the ground they have exactly the opposite effect! Free-ranging camels wander up to 70 km per day in search of grazing, so its not cruel to make them walk. But lifting them by crane into trucks in order to send them back to Rajasthan certainly is, as it damages their digestive system and often leads to death after a few days. We have observed this in camels that were ‘rescued’ from slaughter and transported by truck back to Rajasthan.

Follow

Follow