Today is the start of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP) – hoorrah! And this inspires this blog today which is a continuation of the last one in which I hypothesized that probably, because of their biological/physiological characteristics, camels are not suited for management in large confined holdings where they can’t graze/browse, and are fed with cultivated feed. Such enterprises are not only problematic from an ecological perspective, but also have a hard time making a profit.

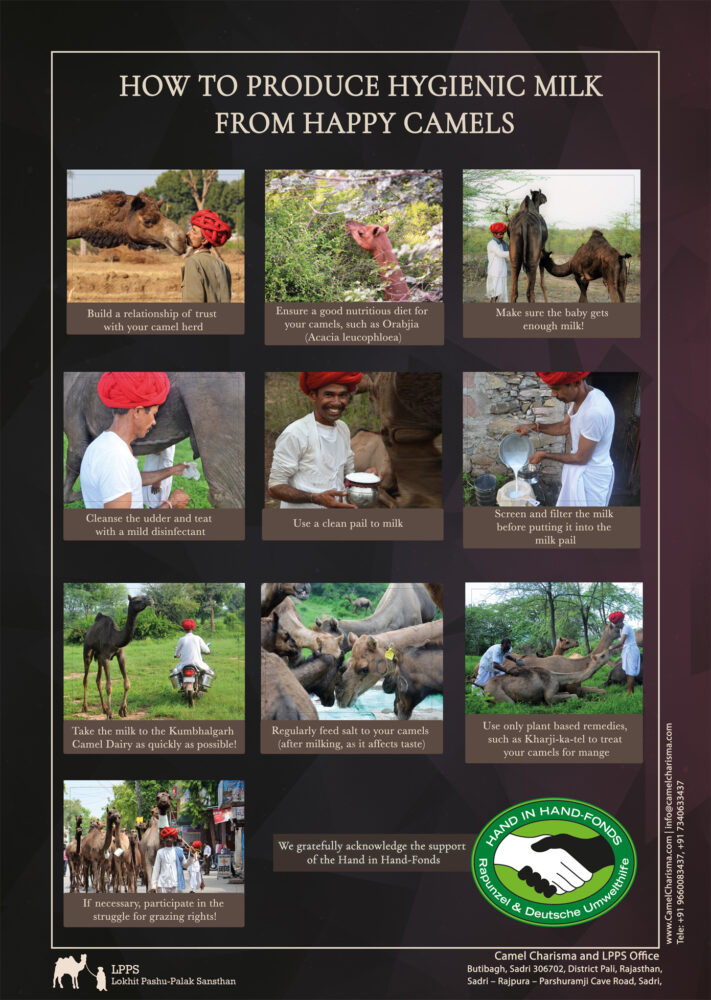

So what is the way forward for camel dairying? This of course depends on the local situation and such factors as the availability of land, accessibility of markets, and cultural attitude towards milk. But I feel very strongly that camel dairying must go along with efforts to regenerate land and restore landscapes (even if on a small scale) so that camels can forage and have something to do and explore, rather than just stand around, be bored, with their existence reduced to synthesizing milk.

I call camels ‘desert gardeners”, because they disseminate and support the germination of the trees and shrubs that they forage on.

Have a look at the photo above. It is an abandoned paddock in which we kept some camels a few years ago until we realized that this stationay system did not work – the camels got infected with mange which we found impossible to control. The Raika told us that they had to MOVE and so we gave them to the care of a herder who wanders around with them.

At the time our small herd departed, there was only bare ground – but now, a few years later, all these shrubs have come up on their own, and – since the photo was taken – grown into a scrub forest. This dense ‘jungle’ can now once again sustain a a certain amount of browsing by camels or goats, representing a perfect circular system! It illustrates the ecological need for camels – and other herbivores – to stay in an area only for a limited amount of time and then move on – for their own health and that of the vegetation! Mobility Matters, as is the slogan for the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists by the International Land Coalition.

The ecology of camels is remarkably underresearched. There were longitudinal studies in the 1960s/70s by Hilde Gauthier-Pilters in the Western Sahara, and in the 1980s/90s by Birgit Dörges and Jürgen Heucke of feral camels in Australia. Gauthier-Pilters noted that camels do not destroy desert vegetation because they disperse widely and take only one bite from a plant before moving on. Doerges and Heucke reported minimal, if any, negative impact of the camels they observed although these were restricted to the same (large) area over years.

Since then, there has been hardly any research on camel ecology. Camel pastoralists of course have lots of observations and are goldmines of information, but, being only sporadically documented, this body of knowledge is difficult to access for most. In India, their observations often refute those of forest officials who blame camels for destroying vegetation, for instance in the Kumbhalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary and among the mangroves at the coast of Kutch. The Raika emphasize that browsing by camels has the same invigorating effect as pruning, causing trees to branch out and develop denser foliage. They also note that camels never go back to the same shrub on the next day, but leave it alone for longer intervals, allowing it to recuperate. With respect to mangroves, the herders believe that camels play a positive role and support regeneration by stomping the seeds into the ground. We need unbiased scientific research to understand and validate pastoralist knowledge before it is too late.

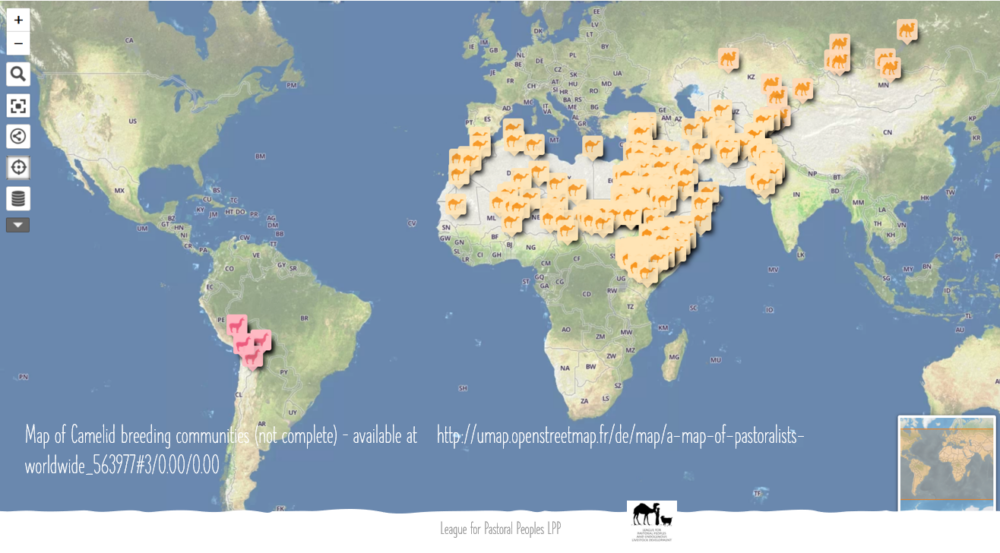

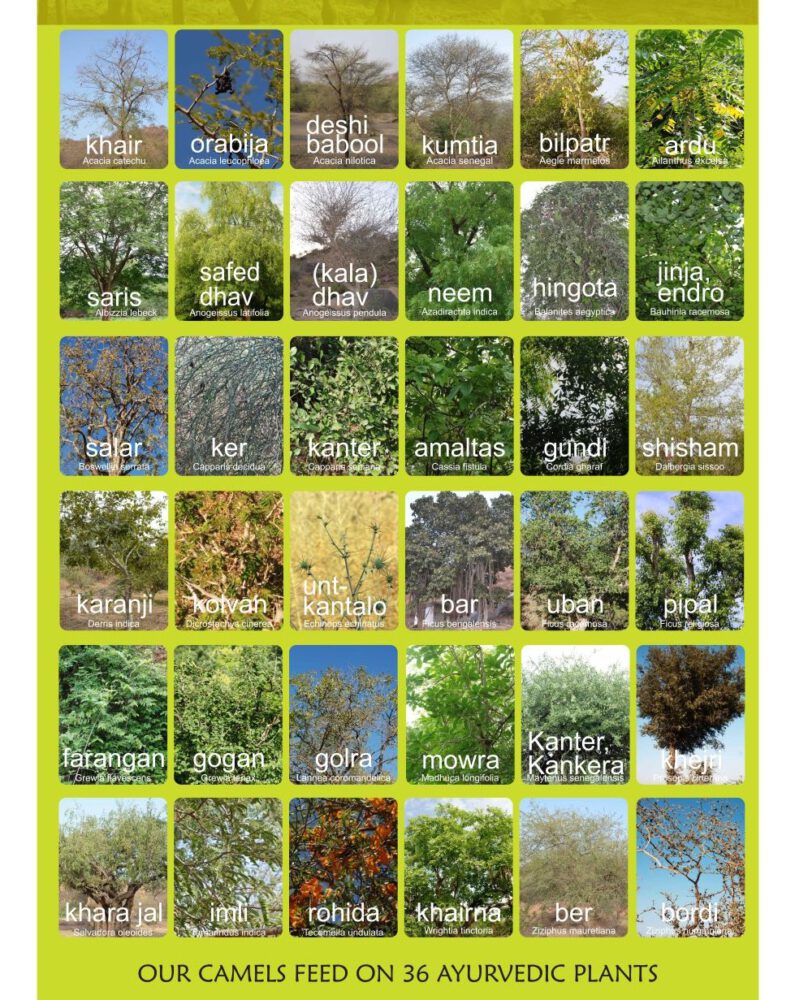

We should make it our New Year’s resolution to always accompany camel dairy ventures with efforts to protect and regenerate the kind of landscapes or browsing patches that camels feel at home in. If they have the option of at least temporarily (part of the day, or seasonally) forage on natural vegetation, it will do so much for their well-being, besides benefitting the quality of their milk – due to the phytochemicals that desert adapted camel forage plants are rich in. In addition, such initiatives will support carbon sequestration, create habitats for other animals, boost biodiversity – a multi-win situation! Silvopastoralism, the integration of livestock with forests, is big in South America – we need to take a slice from there and adapt it to camel countries!

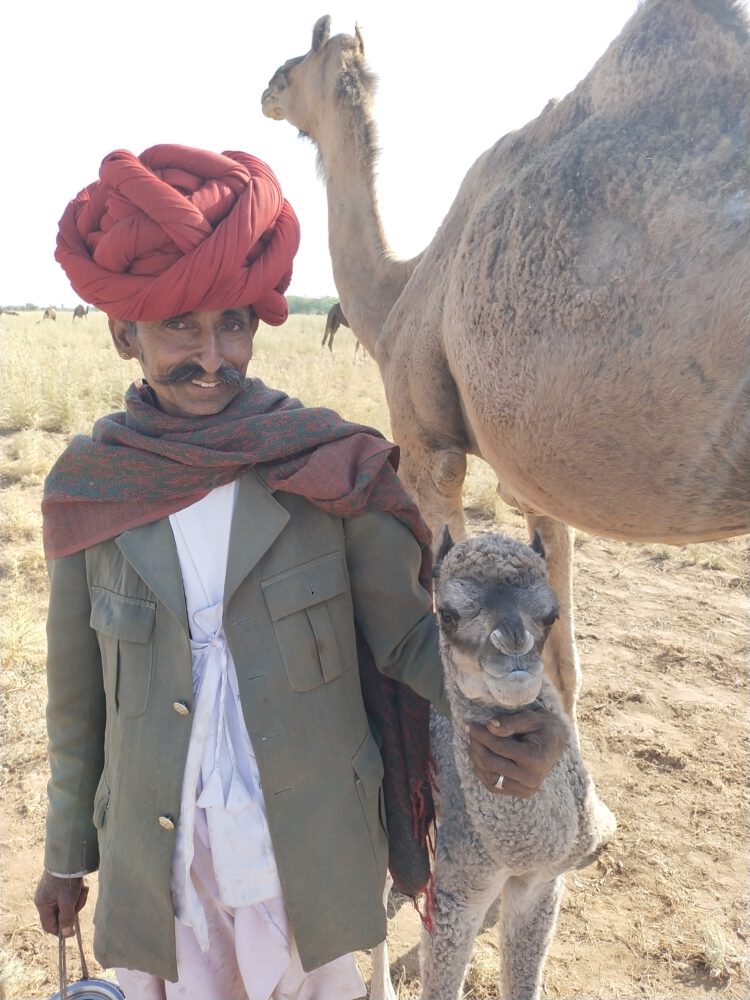

And while I am here, I want to give a shout out to the Raika herders whose camels provide the milk for our social enterprise/company Camel Charisma. They believe that camels browse on 36 different forage plants, all of which are known for their therapeutic qualities and described in the Ayurveda, India’s ancient medicine system. Imagine the goodness of this milk! A precious substance that is produced without any fossil fuels in a completely natural system! It cant get any better than that, and is certainly better than any vegan milk produced from monocultures of almonds, soy or oats.

All camel milk should be produced by happy camels that have the option of going to a ‘park’ where they can stroll around and take a bite from a tree here and there. If our growing camel community adopts such an approach, rather than trying to emulate or compete with the cow dairy sector, then we will have carved out a unique path into the future for our favourite animal!

Lets strive for this in the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists 2026 !

Follow

Follow