The current buzz around camel milk causes a rush of people to enter the emerging camel dairy sector in the belief that it is a lucrative business. This is not necessarily beneficial for camels – nor does it even generate the expected profits – as these new entrants automatically follow the model provided by cow dairies: they search for camels with the best possible yields, confine them somewhere, buy feed, and invest in a milking parlour, with the intent of maximising production. Such industrial scale camel dairies are springing up in oil-rich Arab countries and elsewhere.

Keeping them in confinement subverts the nature and biology of camels – long-legged creatures that have evolved in the most sparsely vegetated environments and are designed to cover huge distances daily to find enough forage to satisfy their nutritional needs under these frugal conditions. We know from the now almost forgotten studies conducted by German biologists Birgit Dörges and Jürgen Heuck in the 1980s and early 2000s, that feral camels in Australia routinely walk up to 70 km per day. Another adaptation of camels to a desert environment is their slow reproduction with a calving interval of two years in most places (it can be less in the Horn of Africa because of two rainy seasons). The camel’s digestive system is aimed at metabolizing extremely thorny, fibrous, salty plants and that is what these animals thrive on and where their ecological advantages lie: producing food in drylands, and without use of fertilizers and fossil fuels.

Coupled with their tolerance of high ambient temperatures, their ability to cope with droughts, and their congenial disposition, camels are evolution’s gift to humanity and a priceless asset in light of the record temperatures that the Earth is currently experiencing in the Indian subcontinent and elsewhere.

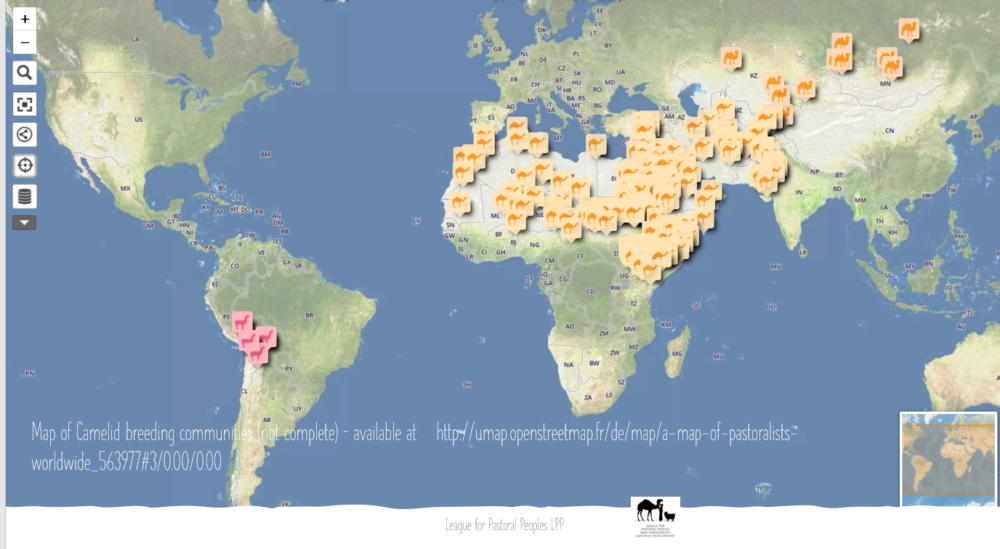

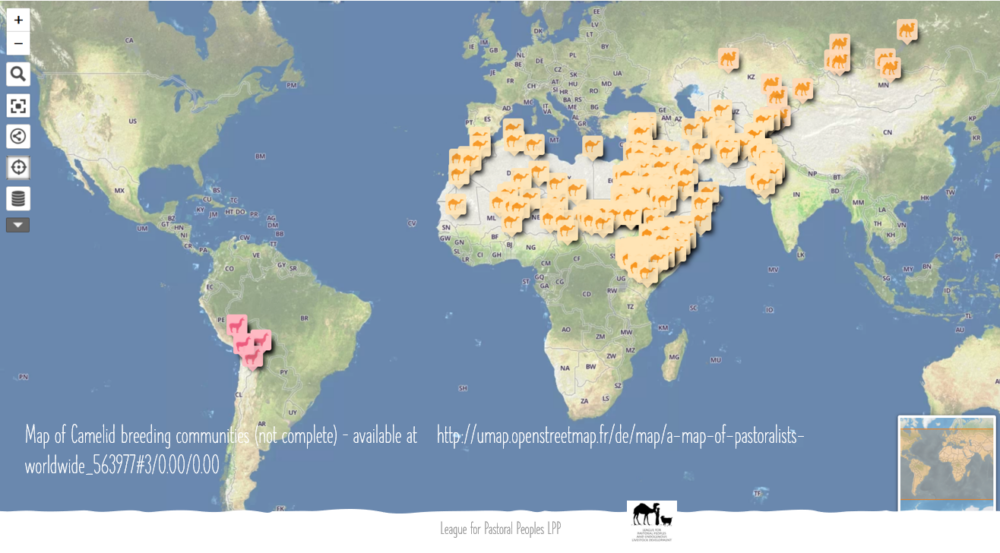

This year we are celebrating the International Year of Camelids, for which the FAO has picked the official slogan the heroes of deserts and highlands that nourish people and culture. Camelids are certainly remarkable, but even bigger heroes are the people that have been stewarding them for thousands of years in extremely inhospitable environments, who have adapted their ways of life to the needs of their camel herds, rather than dominating them.

It is from these societies that we can learn how to keep camels in a way that is basically ethical and long-term sustainable:

- Good for camels by letting them move, keeping them in natural social settings without separating mothers and babies, allowing them to choose their own menus and an environment in which their senses are stimulated.

- Good for people by securing livelihoods, producing healthy food, and not contributing to antimicrobial resistance.

- Good for the environment by nurturing biological diversity, recycling nutrients, replenishing the soil and avoiding the pollution that confined livestock production is associated with.

Of course, pastoralists are not perfect, especially since they are under a lot of pressure in most locations, but their principles of raising camels are basically sound and ethical and the model to follow.

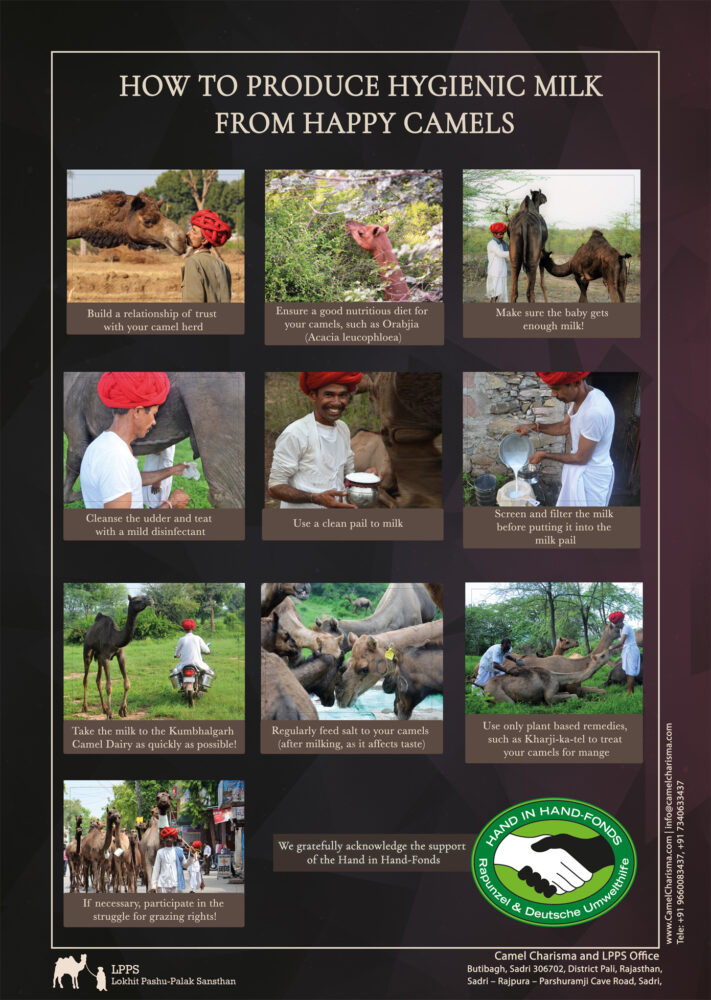

Learning from the Raika camel herding community in Rajasthan, the social enterprise Camel Charisma that I co-founded, is building on their hereditary principles, with some innovations. We support the traditional nomadic system, pay a decent sum to the herders for their milk, and make an effort to provide the most hygienic milk to our customers across India. You can learn about the rationale for the dairy in this official FAO video .

There are other people and communities who have the same approach, for instance Khandaa Byamba and her family in Mongolia who keep Bactrian camels. Even in countries where camels were not traditionally kept, such as Australia, Europe and the USA, efforts are made to keep camels in a more natural, non-industrial way.

Coming back to the on-going International Year of Camelids, its main aim should be to find ways of supporting camel pastoral systems, rather than just focusing on increasing productivity and efficiency. We need an approach that does not see camels in isolation, but in their social and environmental contexts.

In January 2024, camel pastoralists from several countries met in India to exchange experiences and chart out their future work. In their workshop statement they ‘rejected the extractive model of animal production that was superimposed on many camelid-keeping countries in colonial times and is now leading to the capital-intensive industrialisation of camelid keeping, which depends on fossil fuels, chemical inputs and imported feed. At a time when greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must be reduced to prevent further global warming, fossil-fuel-free camelid development that is solar powered, makes optimal use of local resources and is in tune with planetary boundaries is the need of the hour’.

These are wise considerations and one hopes that the people, research institutions, donors that are involved with camels and development take them to heart.

Follow

Follow