FAO Director-General QU Dongyu. ©FAO/Giuseppe Carotenuto

Robyn Alders ©FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

The International Livestock Transformation Conference that took place at FAO Headquarters in Rome from 25-27th September provided plenty of fodder for thought. While it remained hazy which direction the transformation should take – except effecting better production, better nutrition, better environment and better lives – there were many good presentations and one could sense unease with the current thrust of livestock development, especially with respect to antimicrobial resistance and with animal welfare. There was a great presentation by Robyn Alders about the importance of smallholders and how to enhance their access to services and markets. It was also satisfying to see the prominence that was given to pastoralism. Hindou Oumaru Ibrahim of the Association of Indigenous Women and People of Tchad talked about the significance and practical applications of their traditional knowledge, while Mounir Louhaichi of ICARDA emphasized their role in sustainable land managment and that ‘it is not the cow, but the how’ that determines the environmental impact of livestock.

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, Copyright FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

Mounir Louhaichi,

Copyright:FAO/Giuseppe Carotenuto

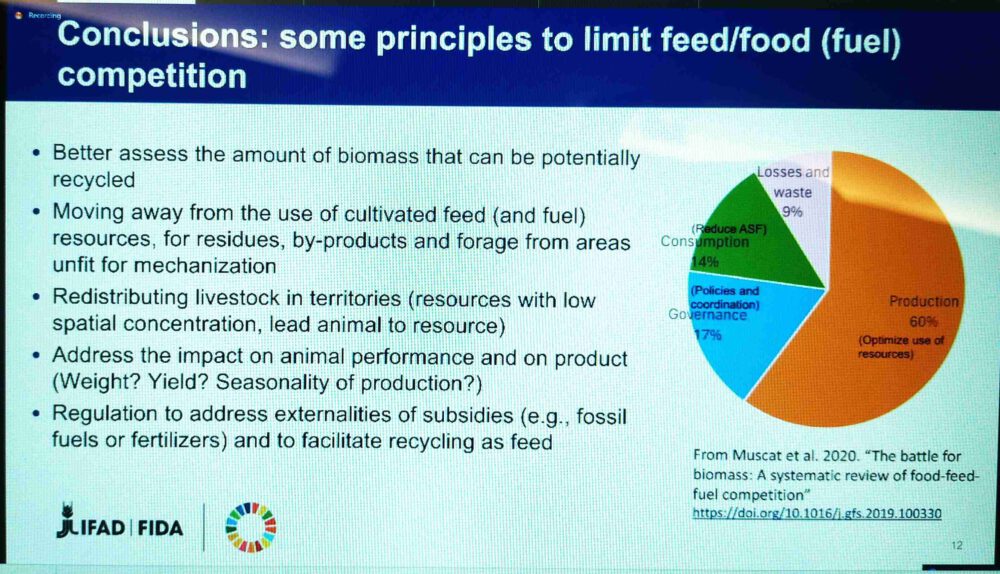

Then there was a noteworthy paper by IFAD’s Anne Mottet about ‘circularity’ with which I could not agree more. In her conclusions, she recommended better spatial distribution of livestock and even ‘leading animals to the resource’ which is basically an endorsement of pastoral systems that embrace both dispersal and mobility.

Anne Mottet ©FAO/Cristiano Minichiello

Circularity! This means reintegrating livestock with crop production to mimic as much as possible natural eco-systems in which herbivores cycle much of the nutrients they uptake from plants back into the soil. In practice, this entails sustaining animals on natural pastures or feeding them with crop by-products, rather than on especially grown feed requiring fossil fuels and chemical fertilizer. In such systems manure once again turns into a very valuable asset rather than the toxic burden it has become in concentrated animals feeding operations.

We must adopt circularity as one of the guiding principles for the design of sustainable livestock systems! It needs to replace the mantra of ‘efficiency’ which merely focuses on product output versus feed input, and ignores the fact that nutrients must be recycled by all means in order to avoid their depletion in the feed producing parts of the world and their toxic accummulation in the feed receiving countries. Arguably, the blinkered focus on efficiency is at the root of the current crisis of Dutch farming. While the Netherlands may have developed (one of) the most ‘efficient’ dairy farm systems in the world, this has also led to the unacceptable levels of nitrogen pollution in soil and water that have caused the current political crisis. They are a result of importing most feed from afar, as the Dutch Minister for Nature and Nitrogen Policy, Christianne van der Wal-Zeggelink pointed out.

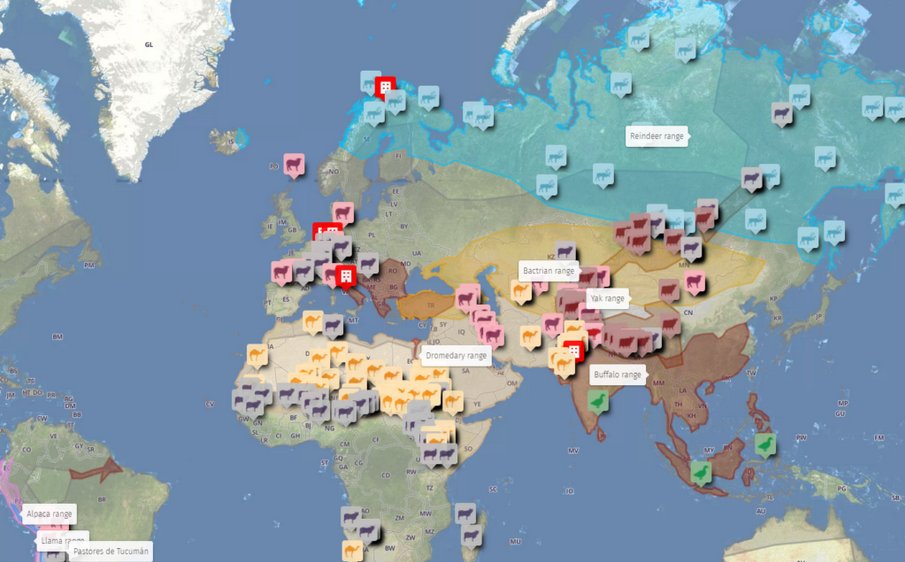

In this context of transforming the livestock sector, a statement by 17 Civil Society organizations at the occasion of the upcoming International Year of Camelids 2024 is noteworthy. Besides calling for ‘Investing in decentralized infrastructure, such as networks of mini-diaries and local processing facilities1 to link camelid herders in remote areas to value chains, while also respecting and supporting our traditional ways of processing,for an alternative vision for the future of livestock, it also advocates for ‘Carving out an alternative, cruelty-free development trajectory for camelid herding that conforms to the worldview of traditional camelid communities and avoids industrialization‘.

There was of also an official side-event on the International Year of Camelids 2024 that was chaired by the governments of Bolivia and Saudi-Arabia and in whichits visual identity was revealed. It had presentations by Mongolia, IFAD, and two genomics experts. Although the IFAD presentation informed about various projects involving camelid herders, communities themselves did not have a chance to speak. Hopefully they will be given a proper platform once the IYC has been officially inaugurated in December. Certainly much can be learned from them on how to best manage ‘the heroes of deserts and highlands’!

Follow

Follow