Camel milk is hyped because of its health value, and as a consequence camel farms have sprung up globally, including smaller ones in Europe, medium sized ones in Australia and huge mega-farms with many thousands of camels in the oil-rich countries. It seems like a race is on to increase milk yields, to select for standardized udders that fit into milking machines, and to promote camel dairy products…… catching up with the cow dairy sector so to speak.

But does it work? Is it financially sustainable? I am beginning to have my doubts after listening to camel dairy owners from various countries that I visited or met on-line recently. I have begun to wonder and ponder whether this is the right way forward. My growing suspicion is that camels are not made for sedentary farming. For one, they are inordinately slow reproducers and they have a looong interval between calvings. Normally they do not lactate while pregnant, so in order to benefit from one lactation, you have to feed the camel for two years – an expensive endeavour if you have to buy the feed.

Secondly, camels are made to walk long distances – feral camels in Australia walk 70 km per day to feed themselves on thinly dispersed vegetation. Fundamentally, they are adapted to scarcity and can not cope that well with abundance.

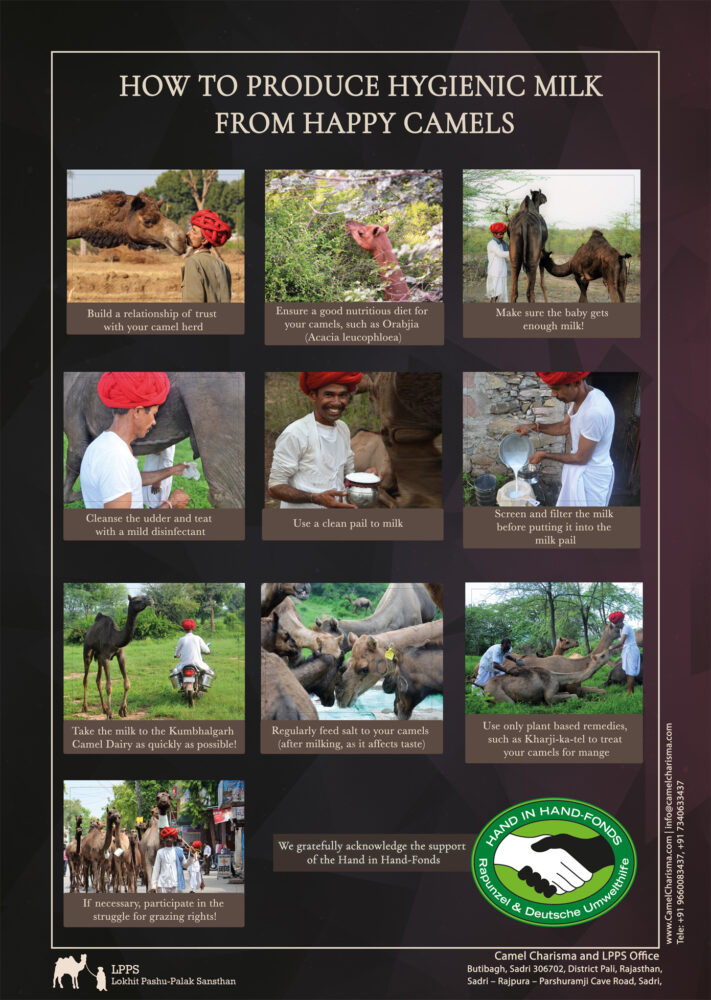

This brings us to the third point: camels LOVE spiky, thorny, salty vegetation, such as acacias to browse on and are not really keen on bland food at all. My good friend, the global camel expert Dr. Raziq Kakar, once compared them to South Asians, who like only spicy food. Sure, they eventually get used to alfalfa hay or other cultivated feed, but how does this affect their health (and the quality of the milk) ? Do we have data on the longevity of camels under different management systems?

Then there is the widely acknowledged problem of the lack of a market for camel milk, except in countries like China and Kazakhstan. Selling the milk produced seems to be a big challenge, because of the price for one, but also for cultural reasons.

So why do it? Why go to the trouble and expense of setting up a farm when the milk does not sell? Even in a country like the United Arab Emirates where camels are beloved and deeply embedded in popular culture, camel milk makes up only 0.4% of total milk consumed, at least according to official data.

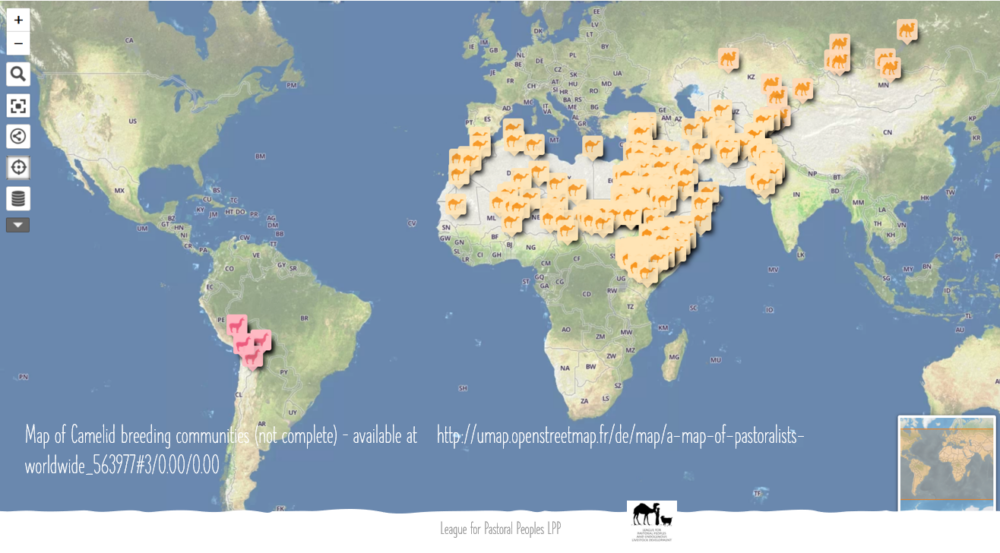

On the other hand, there is the success story of camel milk in East Africa where camel milk is produced in a moral economy as described by Dr. Taheera Mohamed. Here camel dairying thrives, due to a number of factors. Somali people have a cultural affinity to camel milk and prefer it over cow’s milk, so there is a ready market. They also have a taste for fermented milk which lessens hygienic requirements. Women play a crucial role of connecting producers and consumers, and camels are kept either in pastoralist or peri-urban systems. They might be confined while lactating but move around when pregnant which is good for their health andd reduces costs. These informal systems work! This is reflected in the growing camel population numbers in the Horn of Africa where previously cattle herding communities switch to camels to weather the droughts and climate change. Marketing camel milk according to ‘western’ standards may not work, but the role of camels in local food security is enormous.

I am writing about this based on my own experience of setting up a small camel dairy in Rajasthan that has the goal of creating income for Raika camel herders and conserving both Rajasthan’s camels and unique camel culture. We have learnt many things the hard way. We gave up keeping camels on site in a paddock because mange became impossible to control, and there was a problem of feeding them. Our Raika partners insisted that the camels needed to move and we had to let them go to certain grazing areas at particular times of the year. Now all the camels that produce milk for our dairy are herded, keep moving from place to place, and feed on natural vegetation.

But the problem of marketing the milk has only partially been solved. There is a lot more milk available than we can sell. And even though it the price is high, it does not even cover the costs. Only people with health problems who buy it for medicinal reasons are willing or able to go to the expense.

So what is the solution? I will expand on this in my next blog. For now I had to air the idea that camels, as natural ascetics adapted to scarcity, are probably not made for capitalist systems of abundance.

What do you think? Comments are very welcome!

Follow

Follow