Locally adapted livestock breeds are a key resource for adapting to climate change. This is brought home by a recently initiated action research project of Lokhit Pashu-Palak Sansthan (LPPS) that documents and seeks to save an as yet unregistered sheep breed from the Godwar area in Rajasthan. This is the Boti sheep which is distinguishable by its small tubular ears and black head, as well as its lustrous carpet wool. This breed was described already about ten years ago by a Dutch researcher, Ellen Geerlings, who noted that it was gradually being replaced by another breed, the Bhagli sheep, which grows much faster and is therefore more profitable for meat production. The present survey, supported through the FAO’s funding strategy for the implementation of the Global Plan of Action on Animal Genetic Resources is coming just in time: it is hard to find any original Boti sheep at all, as herders have generally been using Bhagli rams. The breed is literally at the verge of extinction.

However, in conversations with the Raika shepherds, they remember very well the advantages of the Boti sheep especially in terms of drought and disease resistance. They emphasize that the Boti breed can endure pain and even if it suffers from Foot and Mouth Disease or has a thorn in its foot, it will continue walking on three legs, while the Bhagli sheep lies down and dies. The Boti can also cope well with rains and water in its pen, whereas Bhagli requires dry ground or will get sick. The ewes of the breed have a very long life span, giving up to 10 lambs.

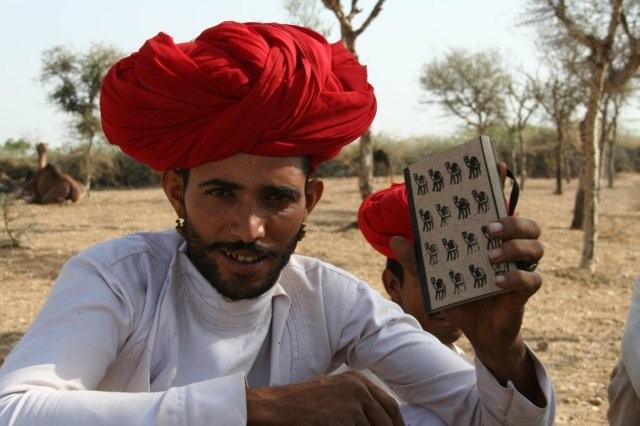

Just by talking about these matters, the shepherds seem to start reconsidering their preference for the Bhagli and express the need to again use a Boti ram (which are however now very difficult to find) for improving disease resistance and drought-proofing their flock. When the possibility is raised that they might receive a higher price for the wool, then they get really interested. Wool prices have been so low that they did not even cover the costs of shearing in recent years. However, through the development of niche markets, for instance by creating rugs that contain both Boti wool and “Desert wool” from the local camels, it will hopefully be possible to create financial incentives for keeping Boti sheep.

So, although the initial results of the survey were depressing, it now looks much more hopeful. Value addition is the way to go for saving breeds and creating high value livestock products that appeal to the discerning customer. My next blog will be about our efforts to develop innovative camel products and how this is benefitting women and “poor” people in the Thar desert.

Follow

Follow