Australia.

In my quest for a solution to Rajasthan’s camel conundrum I absolutely had to go there.

What’s the camel conundrum? Well, in brief, it’s the gloomy camel situation in Rajasthan: despite slaughter and export being prohibited, despite being a draw for tourists and even being protected as state animal, camel nmbers are depleting rapidly.

Paradoxically, in Australia the opposite seemed to be the case: Despite its feral/wild camels officially being classified as a pest and gunned down from helicopters and its meat being used for pet food and exported internationally, its population is thriving.

So why is that? Is there anything to be learnt from Australia? Are wild camels happy – as long as they are not being shot ? Happier than domesticated ones kept in “captivity”? Since many animal welfare people believe we should just stop using animals and let them live “naturally”, this issue interested me.

So there were many questions swirling around in my head when I recently embarked on a trip which provided me with at least a little bit of insight. In this I was incredibly fortunate to have the company and guidance of Debi Robinson. With her camel drawn wagon, Debi has been criss-crossing the Australian outback, including the Nullarbor, over the last decades, accummulating camel mileage that dwarfs the trip of the famous Robyn Davidson immortalized in her book Tracks.

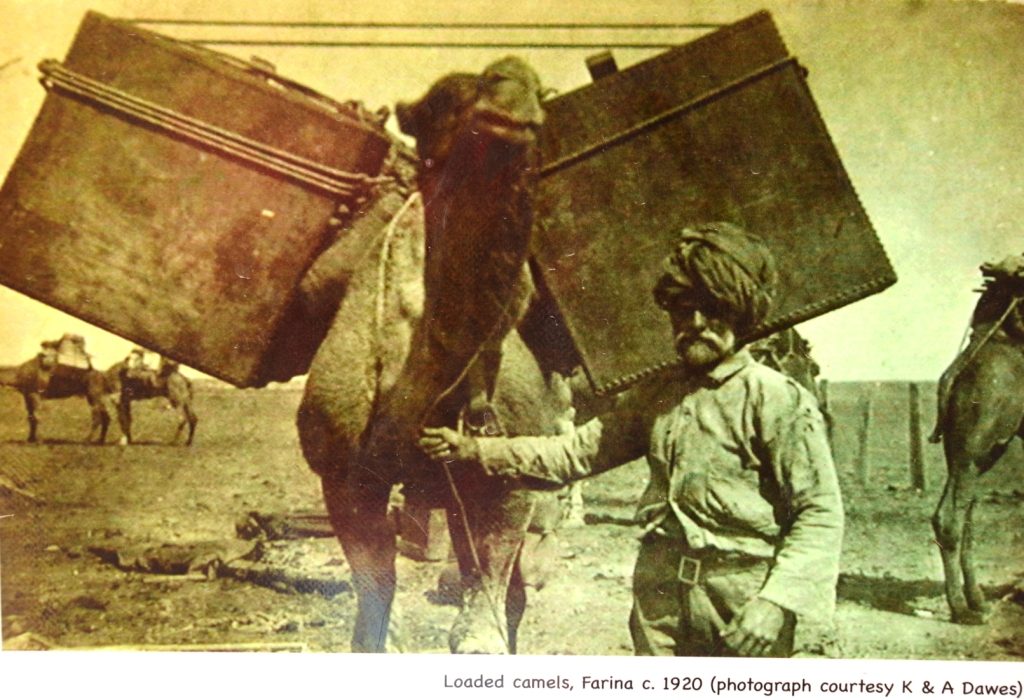

In order to understand the Australian camel situation, we need to insert a quick history lesson here. Camels are of course not native to Australia. But from the 1860s onwards until the 1920s, about 20,000 of them were imported from South Asia for enabling the penetration of the continent, first by explorers than by railway builders and settlers. The initial shipment of camels perished. Realizing that camels on their own were no good and that expertise in camel management was required, the promoters also brought over “Afghan” cameleers on three year contracts. This proved to be an amazing success. Camels took to the arid environment of the outback with its many salt bushes and Acacia trees (called “wattle” in Australia) like a fish to water. Ably managed by their Afghan handlers and owners, they became the engine for establishing footholds in the outback and made it possible to construct the Ghan Railway from Adelaide to Darwin, they transported heavy duty equipment to the sheep stations that were set up in the interior and carried wool back to the ports. The contribution of both “Afghans” and camels to the development of Australia was immense.

Alas, once the railway was built, the camels were deemed no longer necessary by the white colonists and the Afghans were told to shoot them. Many of them refused to do so and instead set the camels free. The camels multiplied quickly and came to be seen as a threat to the sheep and cattle ranchers, breaking fences and causing havoc to watering places. In 1925 a Camel Destruction Act was passed.

By the early 2000s, camel numbers had allegedly gone up to more than a million, so an elaborate plan was hatched to cull 650,000 camels, and this was even justified as a means of obtaining climate credits – as camels are ruminants and belch methane. (As an aside: camels actually emit much less methane than cattle and sheep.) The current wild/feral camel population is estimated to be around 300,000.

Back to the incredible Debi who had kindly invited me to drive up with her from Adelaide to the Marree Camel Race, an annual event initiated to keep alive the memory of the Afghan cameleer community. On the way to Marree we would visit the historic camel places.

Debi, born on a cattle station near Alice Springs, has been with camels all her life, and because she knows that camels need to walk to be happy, she has adopted a nomadic lifestyle herself, even bringing up her five children on the move. She makes and repairs saddles and is an expert in harnessing camels, she speaks an Aboriginal language being brought up mainly by an Aboriginal couple, and she knows about bush tucker. In short, she is a living dictionary of outback ethnobotany, anthropology and history – besides being a wonderfully attentive host.

After meeting up in Burra, we drove straight north, more or less along the railway tracks. Crossing the Flinders Ranges, we camped at Beltana Station where Thomas Elder once embarked on systematic camel breeding, stopped at Farina, the home of the legendary cameleer Gul Mohammed, before we finally reached Marree where we saw the remains of the mosque built by the Afghans – indistinguishable from abandoned mudbrick buildings in Rajasthan.

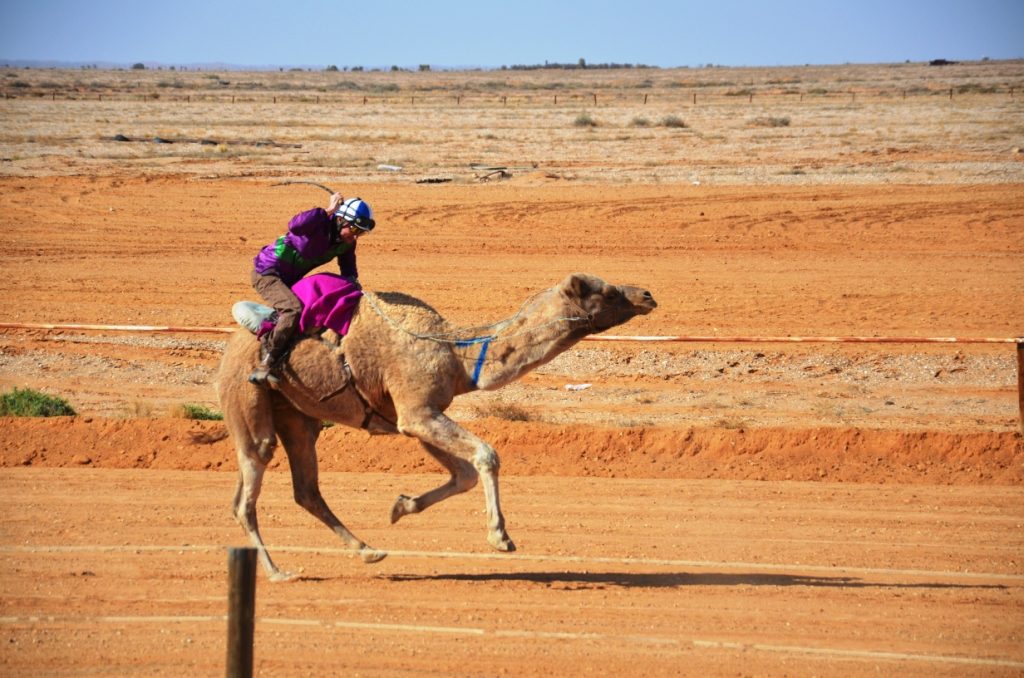

Although the initial motivation for setting up the Marree Camel was to keep alive the memory and culture of the Afghan community, not much of that seems to be left. There were 11 races over distances ranging from 200 m to 1000 m, and a total of about 20 camels competing. One of the races was reserved for Afghan descendants, but the show was dominated by teams of owners, trainers and jockeys who normally make a living from providing camel rides and for whom the races are a hobby.

Debi set up a lovely little circus tent with a variety of camel design arts and crafts, including drawings by Australian artist Malcolm Arnold. Many people were interested in the saddles she builds and repairs – the light weight models definitely an improvement over the heavy weight traditional saddles I know from India. It would be lovely to have her come over to India and share her skills in this respect – it would be to the benefit of camels used in the tourist industry!

I asked Debi what she thought about the culling of camels and, given her deep love for camels, I expected her to totally denounce it. But her answer was much more balanced. “During drought years, the wild camels suffer tremendously and it is kinder to kill them then to let them die slowly. But the shooting from helicopters is not a clean job; many camels only get injured and immobilized; it is necessary to finish the job on the ground.”

But do camels living in the wild have a good life as long as there is no drought and they are not hunted, I wondered? “About a third of the wild camels are injured and broken – this is due to the constant fighting between male camels. They have broken jaws which prevents them from eating properly so they die a slow and painful death. Basically, the female camels form smaller groups and kick out their male offspring after a certain age. These male camels then form bachelor groups which fight between them, so that by the time they reach maturity only 20- 30% survive. The dominant male, often escorted by a couple of “bodyguards”, then goes around looking for female camels to “steal”, killing all their offspring, geldings and other camels before taking them away. If a human gets in between this, it is often fatal”. Debi related harrowing experiences with wild male camels trying to steal her wagon camels while she was on a trek – and how she captured and tied up one of them caught during the act!

For somebody from Rajasthan this was hard to believe. As a rule, male camels are not castrated here. They are well controlled – by means of the nosepeg – and dont get the chance to fight among each other. And it occurs very, very rarely that people get attacked by camels – only when they have been mistreated.

For the Australians on the other hand it seemed incredible that in India uncastrated male camels are deployed for riding and draught and that this works very well – as long as no female is around.

At the end of our trip I asked Debi for her recommendations on how to keep camels happy:

Debi’s Recipe for happy (ier) camels in Australia:

- Set aside a huge piece of land where camels can roam freely. The Aboriginals are grateful if people take a lease of their land and develop local jobs and income.

- Manage these camels, by castrating male camels that are not needed or desired for breeding, and establish a breeding programme – currently Australia does not have any particular breeds; they are a hodgepodge of many different strains, although in some places fairly pure types still exist.

- Set up a camel research centre which also teaches how to handle camels safely and benignly. A lot of mistakes are made out of ignorance.

- Bring in expertise from foreign countries with a longer camel experience.

- Revive the traditional crafts associated with camel handling, such as saddle and harness making.

- Camels have to be kept moving and working. If kept in an enclosure without work, they change their frame of mind and start misbehaving.

- Set up spots for tourists and prospective camel owners where they can observe and learn how camels behave.

I deeply appreciated these words of wisdom from a true camel nomad. Stay tuned for my next blog when I will share my impressions of another aspect of Australian camel culture: its emerging camel dairy sector!

Follow

Follow

Very good insight about the Australian camels. Wish to hear also about the emerging dairy role of camels.

Yes, that will be the topic of my next blog…thanks, Raziq!

Actually, I think Australia may be leadidng the pack in many camel related matters.

Loved reading about your adventures in the land down under Ilse. Its so beautiful in the country . Be interested to know where you can buy camel milk in Sydney. Look forward to your next blog cheers Janice

Dear Janice, thanks! Let me research where there are any camel dairies near Sydney…the ones I visitd are near Brisbane, but there are about a dozen of them in Australia. The milk is however very expensive. but I think its worth it!

Glad to see the use of “Afghan” in quotes, as less than 10% of the imported cameleers were from Afghanistan. The term “Muslim cameleers” is not correct either, if referring to all the imported cameleers, as a substantial proportion were from India, and substantial numbers of those were Hindi etc. So calling the train the Ghan was a furphy!

Also, the camels and their cameleers were not “unemployed” just because of the rail, but the expansion of other motorised vehicles where previously camels reigned supreme. In Central Australia, camels were still being used in some areas into the early ’60’s, three decades after the rail reached Alice Springs.

Thanks, Rod, for those comments. I would love to have some more information about the cameleers that were from India. Are any details available? Since most of the camel breeders in India are Hindus, I would presume there were quite a few Hindus.

I am yet to see an Australian Cameleer with a Hindu name. Almost all of them were Muslims from North Eastern part of British India which is present day Pakistan.

Yes, they were mostly from Afghanistan, Pakistan but few also from Rajasthan. Not sure about Hindu names.

The cameleers were from India, Pakistan, Baluchistan, Afghanistan and Persia (Iran). See https://www.southaustralianhistory.com.au/afghans.htm

They comprised Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus.

Dear Ilse,

one more of your adventurous new experiences! I find these informations you got by the impressing Debi very interesting and I am looking forward to the dairy ones.

All the best

Tita

Where was the first picture (camel and pyramid like hills in the background) taken? I wish to visit that place one day

That is Q Camel Dairy and I think those are the Glass Hill mountains in the background.