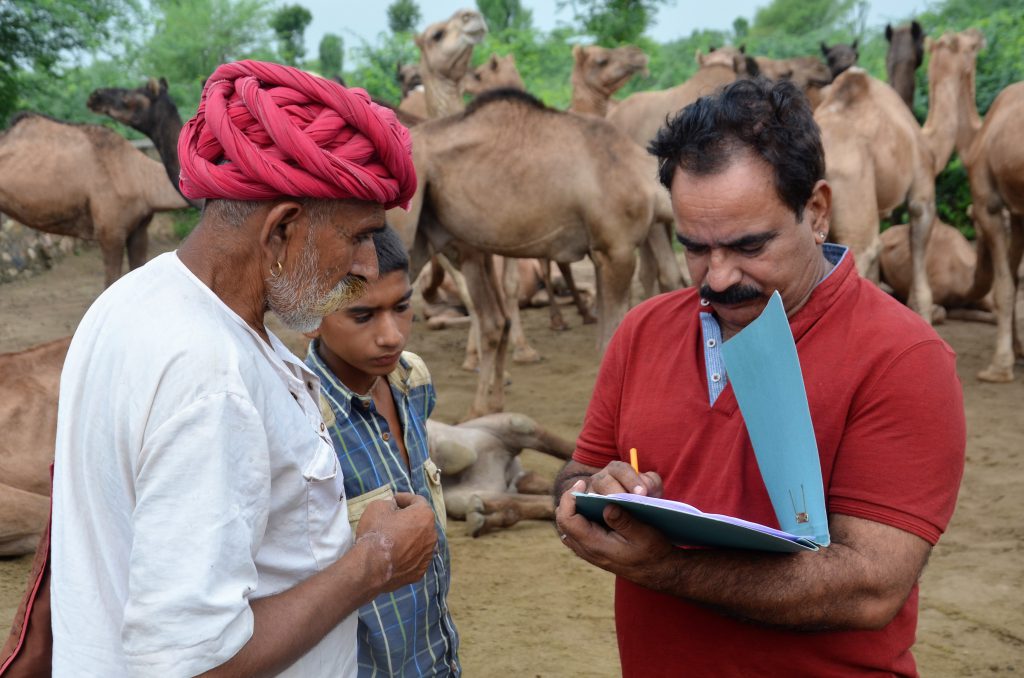

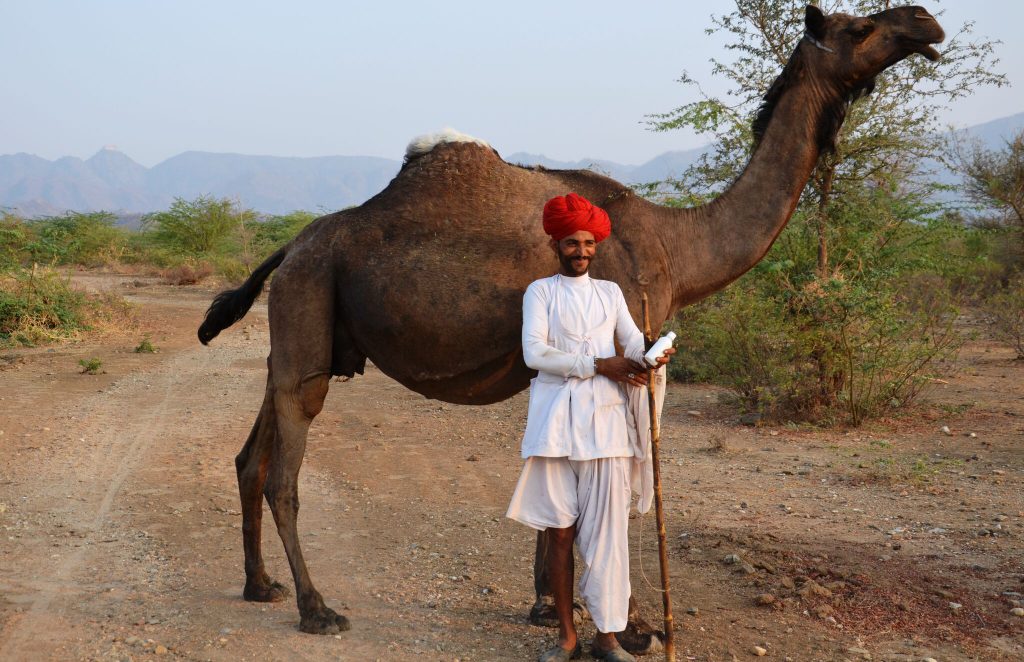

The news about Rajasthan’s state animal is depressing and heart-wrenching: According to the just released official livestock census of India, the country’s camel population has decreased by 37.1% since the last survey in 2012 and is now down to 250,000 (compare that to 1.5 million camels in the late 1980s, and the fact that camel numbers doubled in the rest of the world!). This has happened despite various protection measures having been put in place by the Government of Rajasthan after the previous census in 2012, such as a law prohibiting slaughter and movement across state borders.

In less than two weeks, the Pushkar Camel Fair will attract thousands of tourists who come to visit what is still as billed the world’s largest camel fair, even though it has turned into a horse and amusement fair; the famous camel hill has been annihilated by helipads and resorts, causing the normally placid herders to stage a rally against these conditions.

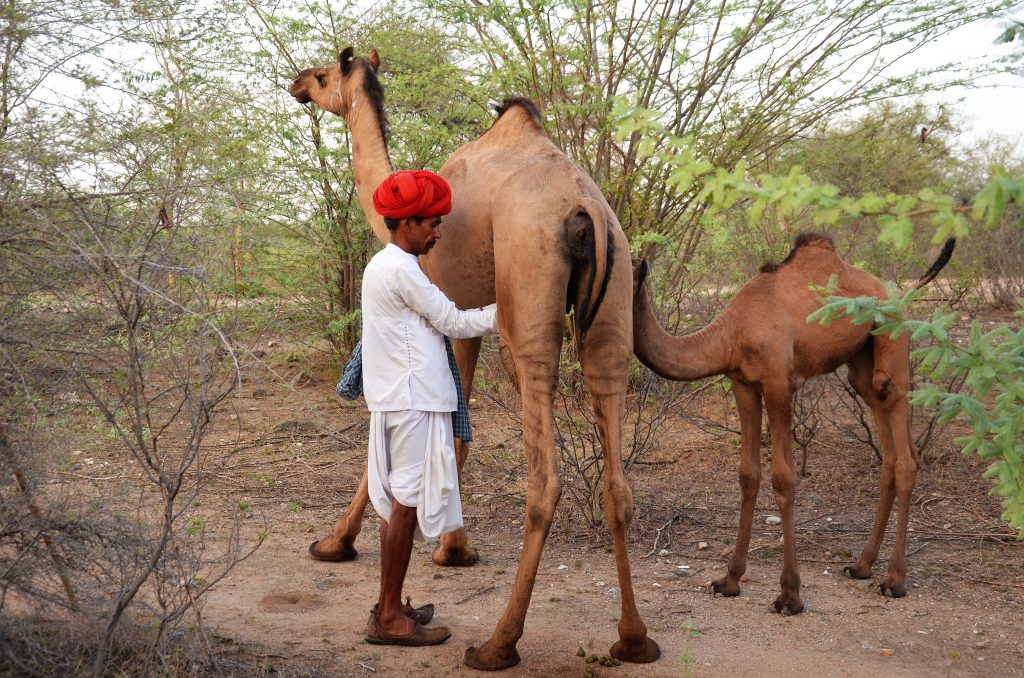

Nevertheless, hundreds of female camels – pregnant, lactating, with babies on foot – are currently being driven to Pushkar in order to sell them off for good. Its an arduous trek over many hundreds of miles and undertaken out of sheer desperation by traditional camel herders who have owned these herds since many generations, but who can no longer make a living from them. Although it breaks their hearts to sell off their ancestral herds, they get pressured by relatives to take this final step and exit herding. Its not just the camels and the livelihoods that are vanishing, but a whole eco-system of community knowledge and mutual support. It takes a community to raise camels!

Over the last few years many of them have held on to their herds hoping that a market for camel milk would develop. But this has not materialized, except for a lucky few who live close to the Kumbhalgarh Camel Dairy on the campus of LPPS in Rajasthan’s Pali district and of which I am a founder. Since it was set up, we have been getting dozens of phone calls every week by Raika begging us to purchase their milk. But despite our best efforts, we have not been able to raise turn-over and only a handful of camel herders have benefited. The milk is marketed mostly directly to the end consumer (80% of them are parents of autistic children), frozen and shipped in ice containers.

There have also been efforts to link up with supermarket chains, but this is expensive, and our start-up has not had the necessary resources, in addition to the logistical challenges. I am convinced that camels are the dairy animal of the future, given the steady rise of temperatures and sinking water levels in Rajasthan and many other parts of the world. They are worthy of investment by all the institutions that concern themselves with food security such as FAO, ILRI, IFAD, WFP. Sadly, none of these is somehow in a position to help support a system that provides livelihoods, saves biodiversity and produces incredibly nutritious food that seems to be an antidote to industrial diets.

In the last few years, animal welfare organizations have spent a lot of money on confiscating camels from places such as Hydrabad and then trucking the poor camels back to Rajasthan ‘where they belong’, and this is the kind of story that gets a lot of media attention. But its not a success story – although the camels may be saved for the moment, what is happening to them in the long run? For sure, a dedicated camel shelter exists in Sirohi, but its resources are also limited, camels get picked up somehow and again may undergo a harrowing transport to a slaughter house. All this could be avoided! It would be so much more animal friendly, if the remaining camel herders could be PAID a living wage to continue taking care of their herds, at least for another year. Costs would be much less than rescuing and transporting the camels back to Rajasthan and provide for their care in a camel shelter. It remains to be seen if the dedication of animal activists extends to seeing the rationale of such an approach.

Conserving Rajasthan’s camel herds is an investment that surely will bear fruit – socially, ecologically, and in terms of human nutrition and animal welfare – in the long run. There is also reason to believe that it will eventually be financially worthwhile, considering the significant amount of research underpinning the therapeutic qualities of camel milk for diseases, such as diabetes and autism. The ‘magic of camel milk’ is the subject of a new book by American author and autism mother Christina Adams. There are also researchers who believe that camel milk is of special value for tackling air pollution, although this is still to be published.

Another important aspect of camel milk is its very high iron content, indicating that it could be of extreme value in alleviating Rajasthan’s high prevalence of malnutrition: anaemia is present in half of the pregnant women, and 23 percent of children are born with low birth weight. Around 39 percent of children are stunted. If we could link Rajasthan’s camel breeders who sit on about 35,000 liters of unutilized camel milk with government nutrition programs, this would be a win-win situation for everybody.

But this will take time to set up. In the meantime it is urgent to prevent loss of Rajasthan’s camel breeding herds and to prevent unnecessary camel suffering by providing a living wage to camel herders and stopping the sell-out of their herds at this Pushkar Fair.

LPPS and LPP are about to start a crowd-funding effort for this purpose. Stay tuned!

Follow

Follow