Recently I had the privilege to attend a “high-level” meeting between ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research and ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute) bureaucrats and scientists. While interaction between such major institutions is important and necessary, I became a bit concerned about the underlying tenor of many of the presentations. For instance there were remarks about farmers/livestock keepers having no concept of animal nutrition and not being able to “calculate rations”. And there is this general attitude of believing that the farmer/livestock keeper is backward, illiterate and in need of guidance by scientists. Well, nothing wrong with science, but how many of the interventions developed by scientists are actually taken off the shelf and being put into use? And, considering that India is not only the largest dairy producer in the world, but also all set to become the global leader in beef exports , must the country’s livestock keepers not be doing many things right? Especially since this development has happened without any noteworthy extension activities, without animal health services reaching the more marginal areas, and without India (yet) becoming dependent on imports of feed stuff from other countries?

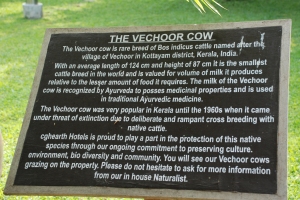

In fact, in my view, India’s livestock development trajectory is exemplary, as compared to a country such as China which, in the course of its Livestock Revolution, has become heavily dependent on import of soy and maize to feed its farm animals. This is because India’s non-poultry livestock production is still largely in the hand of small farmers and pastoralists who make optimal use of locally available feed and fodder resources – both crop by-products and natural, very bio-diverse, vegetation – with their indigenous breeds and by means of their extensive experience and willingness to innovate. Let’s ensure that it remains that way – in the interest of national food security, rural employment opportunities and conservation of biodiversity!

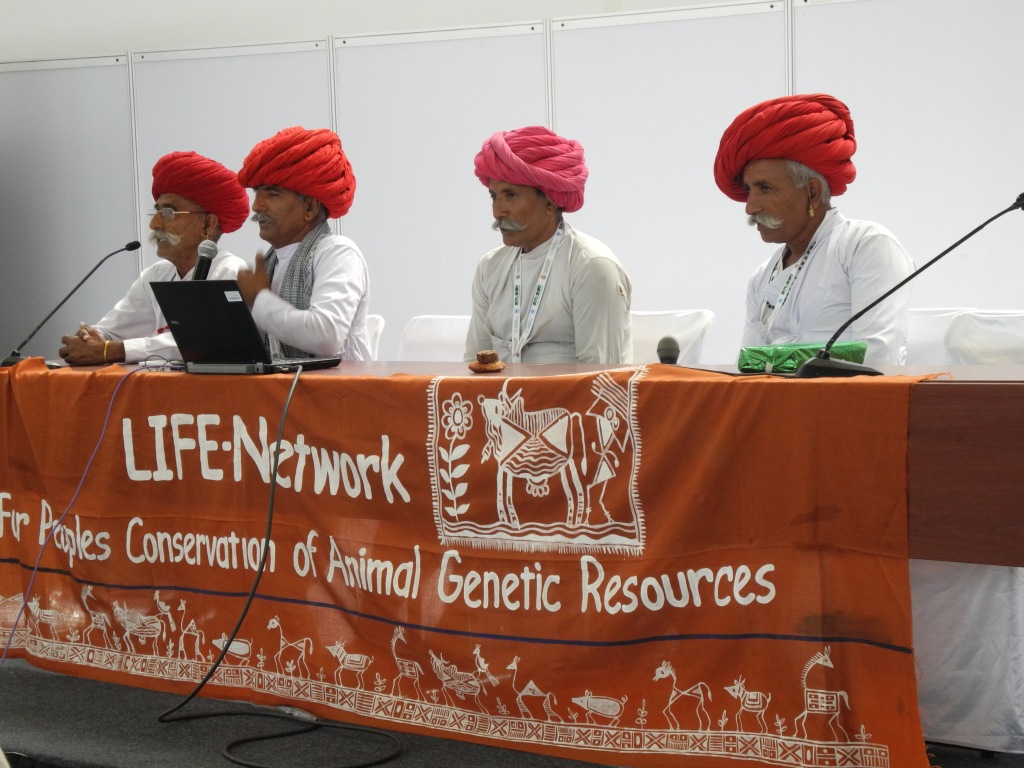

In this context, I must applaud the many members of India’s LIFE Network that work on these lines by respecting and highlighting the value of traditional knowledge, rewarding saviours of local livestock breeds and supporting the struggle for continued access to the Commons and for Forest Rights. See, for instance the tireless work of Dr. Balaram Sahu, Vivekanandan of SEVA, Karthikeya of the Senaapathy Kangayam Research Foundation, Hanwant Singh of LPPS, and many many more.

I send my happy Diwali greetings to all of them and wish them all the best in their endeavours that are so crucial for putting livestock development on a sustainable path!

Follow

Follow