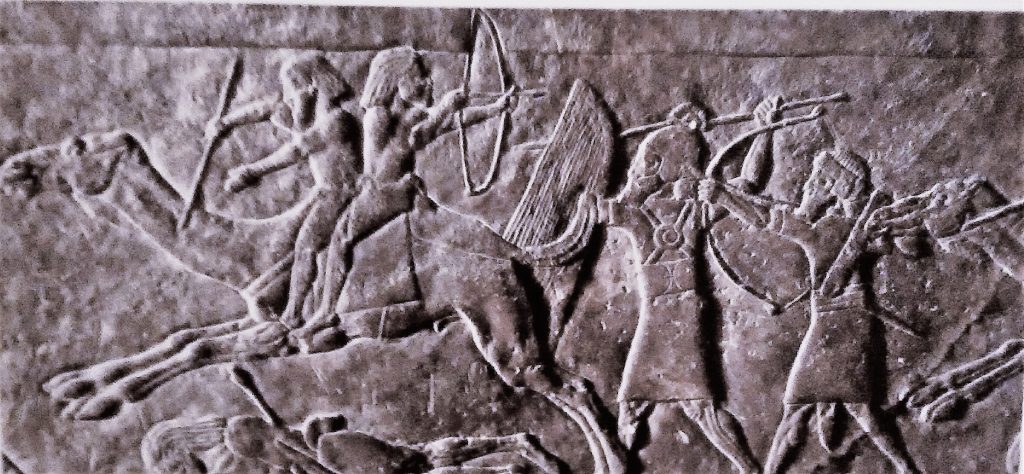

When I recently had the opportunity to travel to Saudi-Arabia, I jumped at the chance. After all, this country is the cradle of camel culture – the place where the human-dromedary relationship was first forged, more than 3000 years ago, and resulted in an amazing technological innovation: warfare from camel back! It was in the battle of Qarqar in 853 B.C. that the ‘Arabs’ first appeared as a distinct group in world history as camel mounted warriors that fought against the Assyrian king Shalmanesar III.

So the emergence of Arab civilization and the domestication of the camel are closely interlinked and cannot be separated from each other. I have always been spellbound by Bedouin camel culture has always enthralled me and I have long been a fan of the explorers, such as Anne Blunt and Alois Musil, that described its fondness and love of camels.

The trip was brought about by my archaeological first life and provided me the incredible fortune to visit some of the world’s most stunning archaeological monuments that have so far been hidden and off limits to foreigners, with the exception of a few intrepid explorers, the likes of Ibn Battuta and Charles Doughty. I am talking about Al Ula in Northern Saudi-Arabia, the site of many thousands of rock drawings which provide testimony of the ecological and cultural history of the Arabian peninsula over the last 7000 years or so. This is also where the Nabatean site of Madain Saleh is located as well as ruins from a range of civilizations. The area is presently being developed into a world class tourist destination by the Royal Commission for Al Ula in a massive multi-disciplinary and visionary effort whose first task is to record the cultural and natural riches.

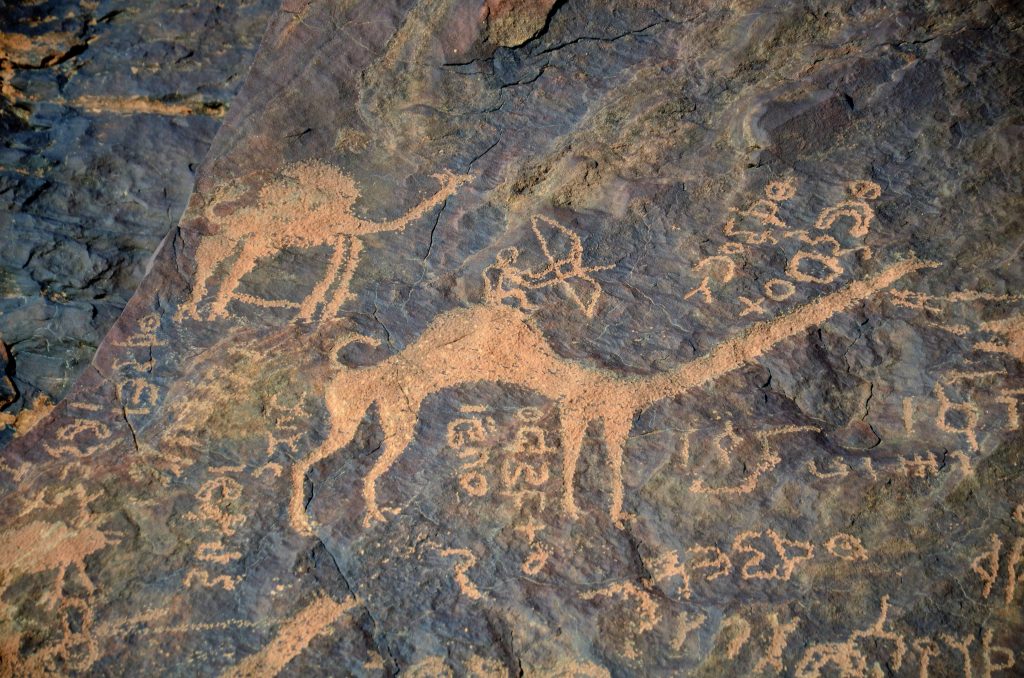

Our journey focused on rock drawings and on the way to Al Ula we stopped at Jubbah, an assemblage of rock formations near Hail which are literally covered in etchings from different periods, mostly of animals. Based on their style, and in combination with various scientific dating methods, archaeologists can tell from which period they are, and the types of animals represented allow us to deduct about the changing ecology of the area. During the Neolithic period – New Stone Age – the environment was clearly much more fertile and similar to what we find in the savannahs of Eastern Africa today: there were lions, baboons, kudus and ostriches. People herded cattle with long, circling horns very similar to those kept by the Dinka people in Southern Sudan today. But after the Neolithic, cattle disappear and camels become abundant. Their appearance is associated with Thamudic inscriptions – Thamudic being a precursor to Arabic.

This replacement of cattle by camels reminds me very much of the processes that are currently going on in Eastern Africa where previously cattle oriented cultures, such as the Samburu and Maasai are switching to camel husbandry because it provides greater food security in times of climate change. In both East and West Africa, the camel distribution range is shifting southwards, as part of a global trend towards increasing importance. Camel milk is gaining recognition in Europe and the US for its health enhancing qualities, but camels should also be of interest to the general livestock sector which worries much about its emissions of greenhouse gases. Camels emit less methane than other ruminants, so it is kind of curious that they are not getting more attention from development agencies.

Travelling with archaeologists, my excursion provided only brief opportunities to see live camels, mostly from a distance.

But the glimpses I caught confirmed that the Bedouin still love their camels, even if they are no longer economically dependent on them, and that these are just as friendly and inquisitive as those kept by the Raika in India. A highlight of my trip was the encounter with a Bedouin near Jubbah who was feeding dates to his herd.

It is very encouraging to know that Saudi-Arabia is set to once again highlight the role of camels in civilization – which is also the theme of the current issue of Aramco World Magazine – through the third edition of the Abdul Aziz Camel Festival scheduled to take place near Riyadh in February 2019. I really hope to be back!

Follow

Follow

Phantastic trip to an area almost unknown to the world and very exciting to find camels paintings even in these ancient archaeological sites in Saudi Arabia! What about consumption of camel milk there nowadays? Like in the UE? Does goverment support camel husbandary? Looking forward to your trip to the camel festival in Riyadh next year!

Very interesting article, but I think there is a problem with the chronology. Everything seems to indicate that the domestication of the one humped camel occurred in the end of the Bronze Age, and the earliest Thamudic inscriptions with the graffiti certainly belong to the Iron Age. This also apply to the Safaitic inscriptions in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula, where we have wonderful depictions of camels, livestock, wild animals, like lion, hyena, gazelle, ostrich and even interbreeding between the one humped and the two humped camel, making a stronger hybrid.

Dear Jorgen,

thanks for your interesting comment. I would love to know more about the depictions you mention, especially of one and two humped camels interbreeding. My impressions are only very superficial, as it was a short trip. I will contact you by email.

Saudi authority currently is trying to protect the fragile ecosystem from overgrazing by limiting the free range pastures to specific zones. Most of the country is arid and plagued by continues droughts in a time of increasing camels herds raised for the purpose of beauty competitions .it is the time that Saudis weather public or private sectors, should start scientific schemes to supplant cows dairy farms products by sustainable camels dairy projects,