It is often said – and given as a reason for disparaging pastoralism – that young people do not want to become pastoralists. Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, that is often the case. Pastoralism is hard work, and in the absence of pro-pastoralist policies while populations grow, it is coming under increasing pressure and in conflict with farmers, roads and urban sprawl. To make matters worse, school education seems to be at odds with herding culture, projecting it as backwards and instilling a sense of disdain of this way of life. This in turn is a consequence of government determined curricula – and we know that hardly any government appreciates pastoralism.

However, the opposite is also true: there are young people that do want to be pastoralists. In developing countries, the motivation may be the absence of better options for making a livelihood. In Rajasthan, I frequently come across young pastoralists who have tried out urban existences but decided that they preferred the independence of pastoralism, despite all the associated hassles. In developed countries, this can also be observed – spending summers up in the Alps looking after goats or cattle and making cheese is quite an attractive proposition for many. Then there are urban shepherds or conservation shepherds who make a living from payments for ecological services or keeping urban lawns short. Or read the bestselling book “A Shepherd’s Life” by James Rebanks, an ode to centuries of rootedness in England’s Lake District.

The world needs pastoralistst, and without pastoralism many countries would starve, especially those with large proportions of uncultivable land. So why is this role of pastoralism not recognized by governments? Why do they not put in place policies that protect pastoralists and make their lives easier, instead of squeezing them out?

I have come to the conclusion that this is because pastoralism operates according to different principles than the animal science based kind of livestock production. Scientific livestock production works under controlled conditions, where everything is predictable – except outbreaks of diseases and prices. There are standardized genetics, standardized feeds, standardized houses and the goal is to maximize output. By contrast pastoralism goes with the flow, it uses the resources that are available and it recycles nutrients into the soil. Pastoralists provide organic fertilizer, they steward livestock genetic diversity, they maintain wild biodiversity. They are usually pleasing to look at while the other type of livestock production has to be secured behind closed doors because people get upset about it.

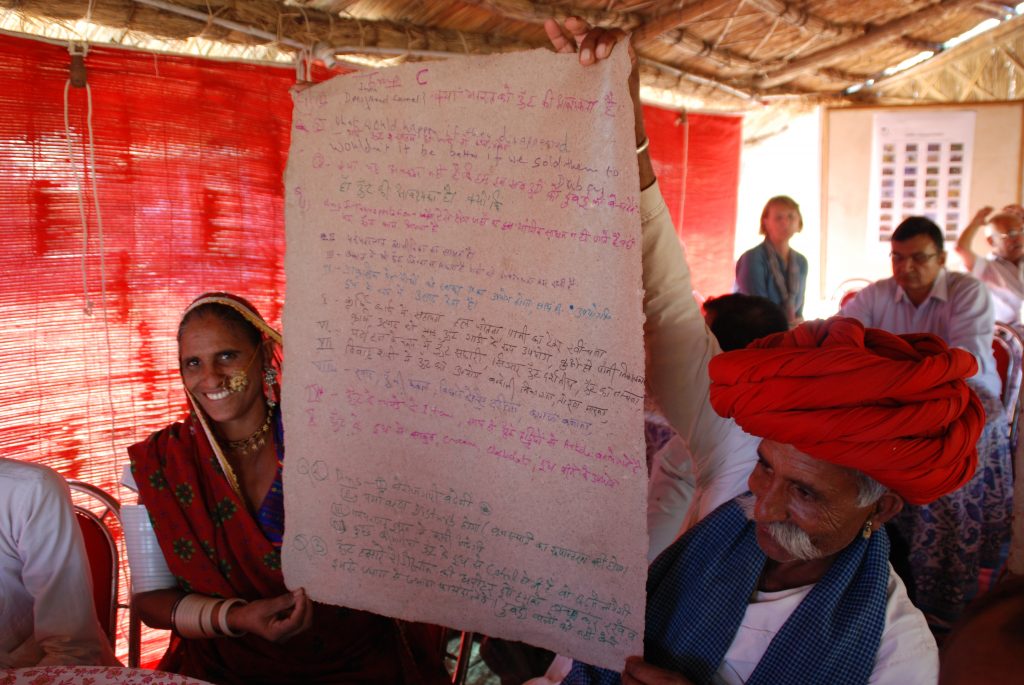

So how to change the mind of policy makers about pastoralists? Well, the only way to do this is to demonstrate and make visible the enormous contributions pastoralists make in terms of food security, biodiversity conservation, and – at least in South Asia – organic fertilizer production. Scientific papers have made a stab at depicting this in numbers, but which policy maker reads them? I believe the most effective way of all is if pastoralist groups or communities themselves record and document what they do for humanity by making use of a tool called Biocultural Community Protocol. Community Protocols are a legal instrument under the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing to the Convention on Biological Diversity, a legal framework that practically all governments of the world are a party to. The Nagoya Protocol commits countries to support communities to develop protocols in which they state under which conditions they would grant access to their genetic resources and traditional knowledge. Now, such “access” can only be provided if these genetic resources (i.e. livestock breeds) and associated knowledge still exist – and without pastoralists managing them in-situ, they certainly will disappear. Ergo, this is the credo of my organization, the League for Pastoral Peoples and Endogenous Livestock Development (LPP) , Community Protocols are a means for pastoralists to firstly describe the resources they manage and secondly to stae te conditions under which they are able and willing to continue this important role for humanity.

Already, more than a dozen of pastoralist communities have developed BCPs, most of them in India, but also in Pakistan, in Kenya, and soon to come in Niger and in Argentina. The more BCPs, the more powerful and difficult to ignore they will become. In September, LPP is organizing a workshop to streamline the metod and process of BCPs, while in late September the Woodaabe of Niger will embark on developing their BCP, using innovative mobile technology. One of these days, governments, international organizations and livestock scientists will listen!

Follow

Follow