Kenya’s camel population has been sky-rocketing in recent decades – from less than one million around the turn of the millennium to an estimated 3.1 million currently. So what’s the secret? Why does the Kenyan situation differ from that in India where camel numbers continue to plummet – despite protection as state animal of Rajasthan and the rescue efforts of animal welfare people? My partner in camel affairs, Hanwant Singh Rathore, director of Indian camel support organization LPPS, and I travelled to Kenya to find out.

We had the good fortune of being hosted by Anne Bruntse, a Danish agronomist who has been residing in Kenya since 34 years, and is a pioneer in camel cheese making. (Her feta, halloumi, and cream cheeses made from the milk of the Kumbhalgarh camels were a hit with Delhiwalas and connoisseurs during the Living Lightly exhibition about pastoralists in India last year). Anne lives on a farm in Gilgil in the Rift Valley and for many years was running a cow dairy and cheese making unit before taking a scientific approach to camel cheese making with a camel-specific rennet invented by the Danish company Chr. Hansen.

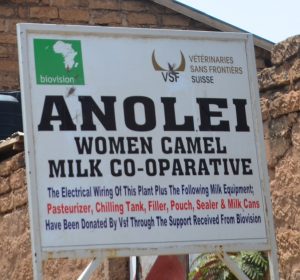

Our first port of call was the Anolei women’s cooperative in Isiolo, a crowded town of mostly Somali residents, about 235 km north of Nairobi.

Somalis are gluttons for camel milk, their whole culture traditionally revolved around the camel, and camel milk is important for their well-being. The Somali women that formed the Anolei cooperative turn over about 3000 liters per day. The crux of the system is the clan system. Somalis sell camel milk only to their clan members and the collective is the link between rural producers and urban consumers. The cooperative organizes the transport to Nairobi and, with the help of donors, has obtained a chilling tank where the milk is cooled down before onward transportation by bus. This makes a big difference to the quality of the milk. The Anolei women also own a pasteurization and filling unit which they are awaiting to operationalize as soon as they receive the necessary certification from the authorities. And, chair woman Sofia Kulow was really excited to share that the cooperative would soon have its own chilling truck to take the milk to Nairobi.

A similar set-up exists in Garissa, another Somali stronghold. Setting up a chilling facility combined with training in hygienic milk collection enormously increased the availability of good quality of camel milk and thereby the demand for it. Local demand by the Somalis is so high that no milk is left over for export to Nairobi!

This is not the only case of camels serving to empower women in Kenya. Laura Llemeneite who has lived among the Samburu tribe for more than 20 years tells the story of how the originally cattle keeping Samburu have been switching to camel keeping in recent decades. Because of a series of droughts as well as climate change, cows are no longer providing enough milk or need to be herded to very distant locations for grazing and can no longer provide milk in the settlements. For the sake of food security, development agencies have been supporting the adoption of camels and distributed over a thousand heifer camels to Samburu women groups.

This has resulted in Samburu women becoming livestock owners for the first time, a change that has considerably strengthened their status in the community. According to Laura, this has led to more eye level marriages, and while the men initially had difficulties accepting that women would attend meetings, they now often even offer to do the cooking so this can happen!

Near Rumuruti we visit Amanda and John Perrett who farm 200 camels on Ol Maisor, a large ranch. Amanda’s father, Jasper Evans, a camel aficionado and visionary established a camel herd in the 1980s, seeing the advantage of combining them with cattle herds to intensify land use: camels and cattle utilize different types of vegetation. In the 1990s, Ol Maisor became a hub of applied research and Jasper also had the foresight to import 60 or so high yielding dairy camels from Pakistan, keeping detailed records about their reproduction, health and veterinary treatments for more than twenty year. This tradition is faithfully continued by Amanda.

Rumuruti is at the southern end of Laikipia district, a place much in the news these days because of conflicts between predominantly white ranchers and conservationists and Samburu or Pokot herders desperate for grazing, with politicians also taking advantage of this situation. So there are security concerns and the camel safaris that were once a major source of income are currently down.

So what is the difference between Kenya and India?

- There is a large Somali community for whom camel milk is an essential food that they don’t seem to be able to do without. Thus there is a significant market for camel milk, providing economic incentives for breeding camels..

- Development organizations have been supporting transition from cattle to camel as a means of drought resilience and climate change adaptation.

- There has been sustained investment in applied camel research and, more recently, in setting up of cool chains to move camel milk from rural to urban areas.

- Women are important actors, including the Somali dairy entrepreneurs, the Samburu household managers, Amanda Perrett, and Anne Bruntse who has not only developed cheese but taught endless courses in hygienic milk collection and processing.

Can some of these approaches be transferred to India? Well, India probably does not have much of a Somali population and thereby an in-built demand for camel milk. On the other hand, people with diseases that can benefit from camel milk (such as autism and diabetes) are numerous there. While switching from cattle to camel is not likely to happen, it is absolutely essential and urgent to invest in the cool chains that link producers with consumers. And an effort should be made to involve women from camel breeding communities. While Indian pastoralist women traditionally have not had much to do with camels (except when going on migration), they have always played the role of “family finance ministers” and may have more of the business sense and attention to detail (hygiene) that are prerequisites for getting India’s camel dairy sector going!

Follow

Follow

Somalis in Isiolo Kenya or Elsewhere have long understood the Importance of Camels. They have now assisted Samburus to also rear camels. Camel is an essential part of Somali Culture. Atleast you mentioned Camel Milk can reduce or cure Autism and Diabetes and is highly valued by Somalis.