Recently I caught up with DraMaria Rosa Lanari, who coordinates the Genetic Resources Network of Argentina’s National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA), when she was on her way to the annual meeting of the EU funded Project on Innovative Management of Animal Genetic Resources (IMAGE). The project which has 28 partners from 17 countries has the aim of enhancing the use of genetic collections and upgrading animal gene bank management.

Q. What is your motivation for participating in this Europe dominated project?

A. It to maintain contacts with other people working on the same issues and staying abreast of the latest developments in the field.

Q. Can you explain what the IMAGE project is about?

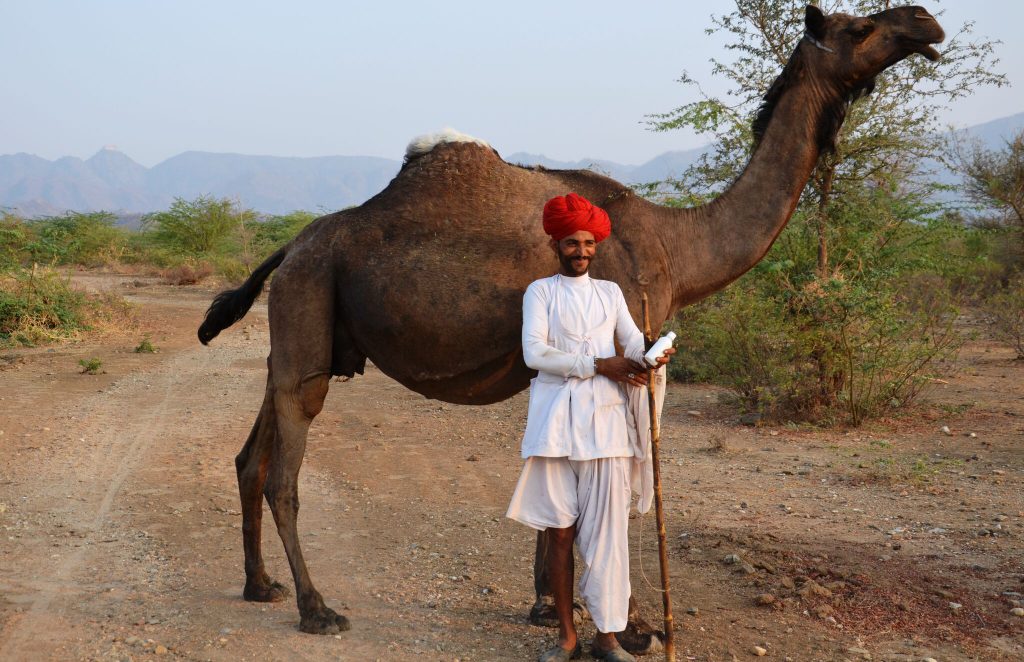

A. It focuses on ex-situ conservation, for instance looking into the problems of keeping adaptive characteristics alive. In Argentina, cryoconservation is not that well developed, we do not have the resources. Only a few local breeds are preserved that way. We putour emphasis on ex-situ in vivo and in situ conservation, meaning we keep goats, sheep, camelids and even bees in their natural ecological context.

Local breeds are really important in all the marginal areas where they are kept by small producers. This project provides us with some visibility for local breeds. We use the funds for capacity building of young people.

Q. You have worked in this field for around thirty years. What have been your major insights?

A. Thirty years ago I also thought that pastoralists are primitive and backwards. This was when I was fresh from university. But now I know different.

Q. Why do we need to conserve local livestock breeds?

The value of the local breeds lies in the fact that they do not cost anything but provide plenty, under challenging circumstances.It is a lie that the commercial breeds are always better. Everybody talks about what they provide and not what they take. They need good feed, shelter and veterinary care in order to be productive.

Q. Can you give us an example that illustrates the value of local breeds?

A. During the eruption of the Puyehue volcano we really saw the value of the local breeds. The volcano was active for six months and the ashes drifted into North Patagonia (Argentina). 70% of the animals of small holders died. So we helped the livestock keepers obtain new goats of the Criollo breed from Neuquen. It was a total success. The people were so happy and they are still happy. Before the volcano outbreak they had kept Angora goats which were not very fertile. Another example from our pampa region is with Criollo Cattle. One farmer told me “I got this cow from an altitude of 4000 meters and brought it to the lowlands. The first year we were flooded and the cow gave birth. The second year, we had a terrible drought, but the cow gave us another calf.”

Usually in emergency scenarios, aid agencies provide commercial breeds. But these animals are not a gift, they are frequently a burden for the new owners.

Q. Can you tell us a bit about INTA’s plans for the near future with respect to local breeds?

A. Our goal is to make visible the advantages of these breeds in terms of cost and benefit of their remarkabletraits as disease or parasite resistance, resilience, adaptation, etc. we have to document and analyze the performance in integral way.We have to look the total system: environmental, social and economic drives are vital.

Another aim is to develop Biocultural Community Protocols to document some of our breeds and their co evolution and interactions with communities. Local breeds are kept by rural communities across the country. In addition to representing biological diversity these Animal Genetic Resources have a cultural and social context, and strong tie to traditional values. BCP allows making visible these significant attributes.

Thank you, Maria Rosa!

Follow

Follow